‘People, ideas, machines — in that order!’ Colonel Boyd.

‘The main thing that’s needed is simply the recognition of how important seeing is, and the will to do something about it.’ Bret Victor.

‘[T]he transfer of an entirely new and quite different framework for thinking about, designing, and using information systems … is immensely more difficult than transferring technology.’ Robert Taylor, one of the handful most responsible for the creation of the internet and personal computing, and in inspiration to Bret Victor.

‘[M]uch of our intellectual elite who think they have “the solutions” have actually cut themselves off from understanding the basis for much of the most important human progress.’ Michael Nielsen, physicist.

Introduction

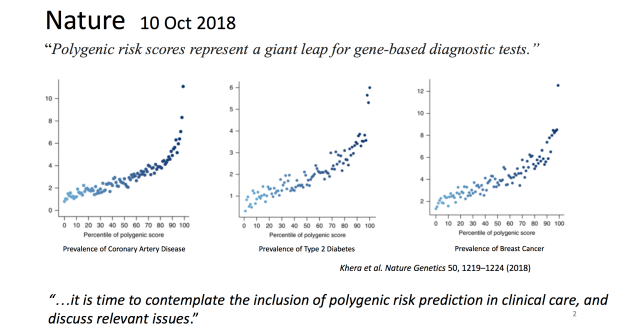

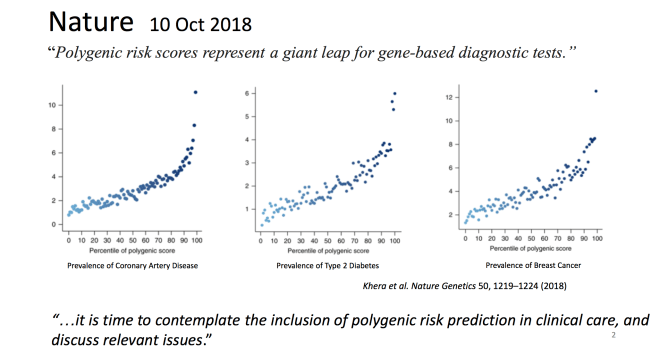

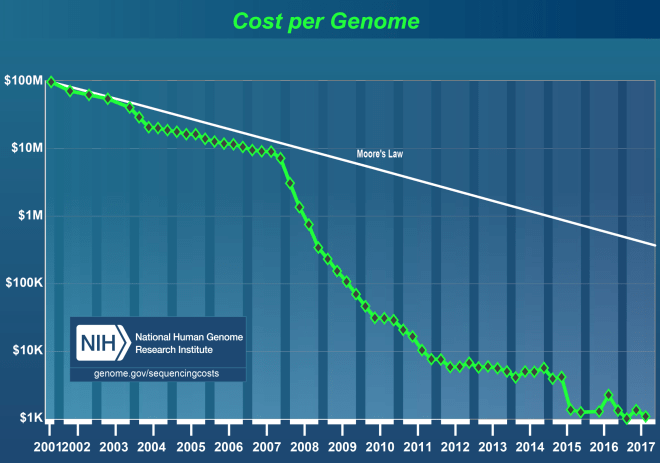

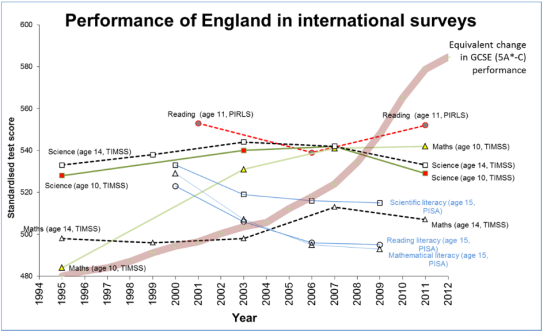

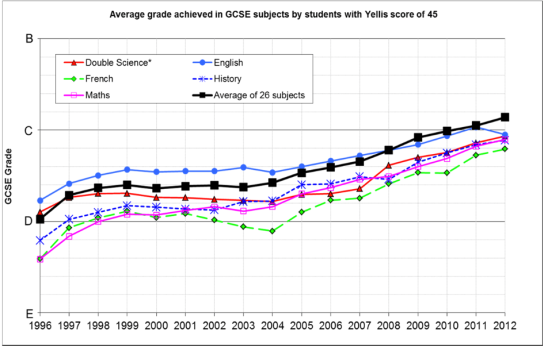

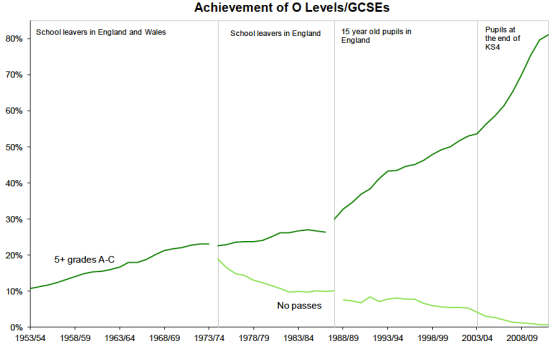

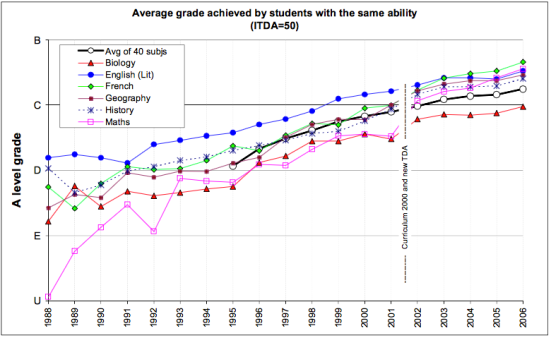

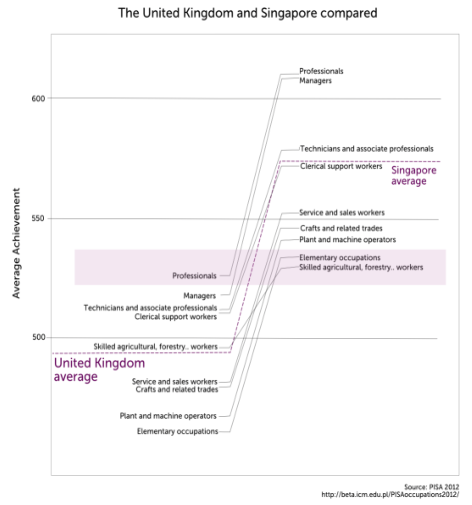

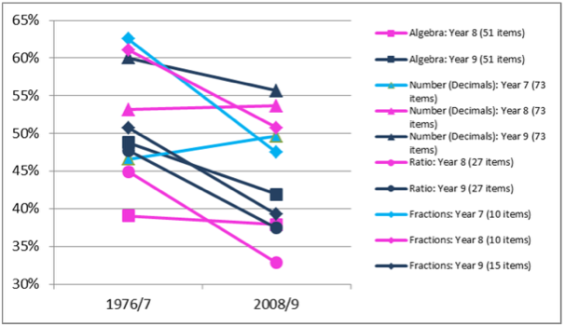

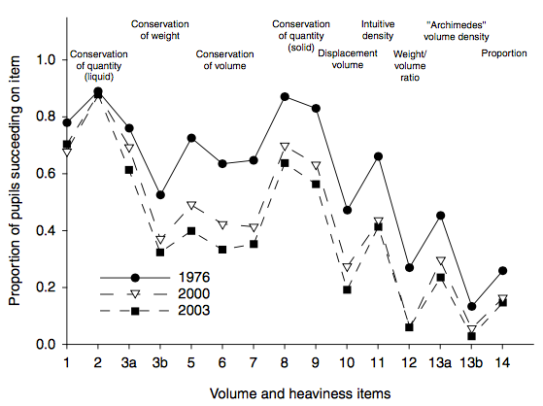

This blog looks at an intersection of decision-making, technology, high performance teams and government. It sketches some ideas of physicist Michael Nielsen about cognitive technologies and of computer visionary Bret Victor about the creation of dynamic tools to help understand complex systems and ‘argue with evidence’, such as ‘tools for authoring dynamic documents’, and ‘Seeing Rooms’ for decision-makers — i.e rooms designed to support decisions in complex environments. It compares normal Cabinet rooms, such as that used in summer 1914 or October 1962, with state-of-the-art Seeing Rooms. There is very powerful feedback between: a) creating dynamic tools to see complex systems deeper (to see inside, see across time, and see across possibilities), thus making it easier to work with reliable knowledge and interactive quantitative models, semi-automating error-correction etc, and b) the potential for big improvements in the performance of political and government decision-making.

It is relevant to Brexit and anybody thinking ‘how on earth do we escape this nightmare’ but 1) these ideas are not at all dependent on whether you support or oppose Brexit, about which reasonable people disagree, and 2) they are generally applicable to how to improve decision-making — for example, they are relevant to problems like ‘how to make decisions during a fast moving nuclear crisis’ which I blogged about recently, or if you are a journalist ‘what future media could look like to help improve debate of politics’. One of the tools Nielsen discusses is a tool to make memory a choice by embedding learning in long-term memory rather than, as it is for almost all of us, an accident. I know from my days working on education reform in government that it’s almost impossible to exaggerate how little those who work on education policy think about ‘how to improve learning’.

Fields make huge progress when they move from stories (e.g Icarus) and authority (e.g ‘witch doctor’) to evidence/experiment (e.g physics, wind tunnels) and quantitative models (e.g design of modern aircraft). Political ‘debate’ and the processes of government are largely what they have always been — largely conflict over stories and authorities where almost nobody even tries to keep track of the facts/arguments/models they’re supposedly arguing about, or tries to learn from evidence, or tries to infer useful principles from examples of extreme success/failure. We can see much better than people could in the past how to shift towards processes of government being ‘partially rational discussion over facts and models and learning from the best examples of organisational success‘. But one of the most fundamental and striking aspects of government is that practically nobody involved in it has the faintest interest in or knowledge of how to create high performance teams to make decisions amid uncertainty and complexity. This blindness is connected to another fundamental fact: critical institutions (including the senior civil service and the parties) are programmed to fight to stay dysfunctional, they fight to stay closed and avoid learning about high performance, they fight to exclude the most able people.

I wrote about some reasons for this before the referendum (cf. The Hollow Men). The Westminster and Whitehall response was along the lines of ‘natural party of government’, ‘Rolls Royce civil service’ blah blah. But the fact that Cameron, Heywood (the most powerful civil servant) et al did not understand many basic features of how the world works is why I and a few others gambled on the referendum — we knew that the systemic dysfunction of our institutions and the influence of grotesque incompetents provided an opportunity for extreme leverage.

Since then, after three years in which the parties, No10 and the senior civil service have imploded (after doing the opposite of what Vote Leave said should happen on every aspect of the negotiations) one thing has held steady — Insiders refuse to ask basic questions about the reasons for this implosion, such as: ‘why Heywood didn’t even put together a sane regular weekly meeting schedule and ministers didn’t even notice all the tricks with agendas/minutes etc’, how are decisions really made in No10, why are so many of the people below some cognitive threshold for understanding basic concepts (cf. the current GATT A24 madness), what does it say about Westminster that both the Adonis-Remainers and the Cash-ERGers have become more detached from reality while a large section of the best-educated have effectively run information operations against their own brains to convince themselves of fairy stories about Facebook, Russia and Brexit…

It’s a mix of amusing and depressing — but not surprising to me — to hear Heywood explain HERE how the British state decided it couldn’t match the resources of a single multinational company or a single university in funding people to think about what the future might hold, which is linked to his failure to make serious contingency plans for losing the referendum. And of course Heywood claimed after the referendum that we didn’t need to worry about the civil service because on project management it has ‘nothing to learn’ from the best private companies. The elevation of Heywood in the pantheon of SW1 is the elevation of the courtier-fixer at the expense of the thinker and the manager — the universal praise for him recently is a beautifully eloquent signal that those in charge are the blind leading the blind and SW1 has forgotten skills of high value, the skills of public servants such as Alanbrooke or Michael Quinlan.

This blog is hopefully useful for some of those thinking about a) improving government around the world and/or b) ‘what comes after the coming collapse and reshaping of the British parties, and how to improve drastically the performance of critical institutions?’

Some old colleagues have said ‘Don’t put this stuff on the internet, we don’t want the second referendum mob looking at it.’ Don’t worry! Ideas like this have to be forced down people’s throats practically at gunpoint. Silicon Valley itself has barely absorbed Bret Victor’s ideas so how likely is it that there will be a rush to adopt them by the world of Blair and Grieve?! These guys can’t tell the difference between courtier-fixers and people with models for truly effective action like General Groves (HERE). Not one in a thousand will read a 10,000 word blog on the intersection of management and technology and the few who do will dismiss it as the babbling of a deluded fool, they won’t learn any more than they learned from the 2004 referendum or from Vote Leave. And if I’m wrong? Great. Things will improve fast and a second referendum based on both sides applying lessons from Bret Victor would be dynamite.

NB. Bret Victor’s project, Dynamic Land, is a non-profit. For an amount of money that a government department like the Department for Education loses weekly without any minister realising it’s lost (in the millions per week in my experience because the quality of financial control is so bad), it could provide crucial funding for Victor and help itself. Of course, any minister who proposed such a thing would be told by officials ‘this is illegal under EU procurement law and remember minister that we must obey EU procurement law forever regardless of Brexit’ — something I know from experience officials say to ministers whether it is legal or not when they don’t like something. And after all, ministers meekly accepted the Kafka-esque order from Heywood to prioritise duties of goodwill to the EU under A50 over preparations to leave A50, so habituated had Cameron’s children become to obeying the real deputy prime minister…

Below are 4 sections:

- The value found in intersections of fields

- Some ideas of Bret Victor

- Some ideas of Michael Nielsen

- A summary

*

1. Extreme value is often found in the intersection of fields

The legendary Colonel Boyd (he of the ‘OODA loop’) would shout at audiences ‘People, ideas, machines — in that order.‘ Fundamental political problems we face require large improvements in the quality of all three and, harder, systems to integrate all three. Such improvements require looking carefully at the intersection of roughly five entangled areas of study. Extreme value is often found at such intersections.

- Explore what we know about the selection, education and training of people for high performance (individual/team/organisation) in different fields. We should be selecting people much deeper in the tails of the ability curve — people who are +3 (~1:1,000) or +4 (~1:30,000) standard deviations above average on intelligence, relentless effort, operational ability and so on (now practically entirely absent from the ’50 most powerful people in Britain’). We should train them in the general art of ‘thinking rationally’ and making decisions amid uncertainty (e.g Munger/Tetlock-style checklists, exercises on SlateStarCodex blog). We should train them in the practical reasons for normal ‘mega-project failure’ and case studies such as the Manhattan Project (General Groves), ICBMs (Bernard Schriever), Apollo (George Mueller), ARPA-PARC (Robert Taylor) that illustrate how the ‘unrecognised simplicities’ of high performance bring extreme success and make them work on such projects before they are responsible for billions rather than putting people like Cameron in charge (after no experience other than bluffing through PPE then PR). NB. China’s leaders have studied these episodes intensely while American and British institutions have actively ‘unlearned’ these lessons.

- Explore the frontiers of the science of prediction across different fields from physics to weather forecasting to finance and epidemiology. For example, ideas from physics about early warning systems in physical systems have application in many fields, including questions like: to what extent is it possible to predict which news will persist over different timescales, or predict wars from news and social media? There is interesting work combining game theory, machine learning, and Red Teams to predict security threats and improve penetration testing (physical and cyber). The Tetlock/IARPA project showed dramatic performance improvements in political forecasting are possible, contra what people such as Kahneman had thought possible. A recent Nature article by Duncan Watts explained fundamental problems with the way normal social science treats prediction and suggested new approaches — which have been almost entirely ignored by mainstream economists/social scientists. There is vast scope for applying ideas and tools from the physical sciences and data science/AI — largely ignored by mainstream social science, political parties, government bureaucracies and media — to social/political/government problems (as Vote Leave showed in the referendum, though this has been almost totally obscured by all the fake news: clue — it was not ‘microtargeting’).

- Explore technology and tools. For example, Bret Victor’s work and Michael Nielsen’s work on cognitive technologies. The edge of performance in politics/government will be defined by teams that can combine the ancient ‘unrecognised simplicities of high performance’ with edge-of-the-art technology. No10 is decades behind the pace in old technologies like TV, doesn’t understand simple tools like checklists, and is nowhere with advanced technologies.

- Explore the frontiers of communication (e.g crisis management, applied psychology). Technology enables people to improve communication with unprecedented speed, scale and iterative testing. It also allows people to wreak chaos with high leverage. The technologies are already beyond the ability of traditional government centralised bureaucracies to cope with. They will develop rapidly such that most such centralised bureaucracies lose more and more control while a few high performance governments use the leverage they bring (c.f China’s combination of mass surveillance, AI, genetic identification, cellphone tracking etc as they desperately scramble to keep control). The better educated think that psychological manipulation is something that happens to ‘the uneducated masses’ but they are extremely deluded — in many ways people like FT pundits are much easier to manipulate, their education actually makes them more susceptible to manipulation, and historically they are the ones who fall for things like Russian fake news (cf. the Guardian and New York Times on Stalin/terror/famine in the 1930s) just as now they fall for fake news about fake news. Despite the centrality of communication to politics it is remarkable how little attention Insiders pay to what works — never mind the question ‘what could work much better?’. The fact that so much of the media believes total rubbish about social media and Brexit shows that the media is incapable of analysing the intersection of politics and technology but, although it is obviously bad that the media disinforms the public, the only rational planning assumption is that this problem will continue and even get worse. The media cannot explain either the use of TV or traditional polling well, these have been extremely important for over 70 years, and there is no trend towards improvement so a sound planning assumption is surely that the media will do even worse with new technologies and data science. This will provide large opportunities for good and evil. A new approach able to adapt to the environment an order of magnitude faster than now would disorient political opponents (desperately scrolling through Twitter) to such a degree — in Boyd’s terms it would ‘collapse their OODA loops’ — that it could create crucial political space for focus on the extremely hard process of rewiring government institutions which now seems impossible for Insiders to focus on given their psychological/operational immersion in the hysteria of 24 hour rolling news and the constant crises generated by dysfunctional bureaucracies.

- Explore how to re-program political/government institutions at the apex of decision-making authority so that a) people are more incentivised to optimise things we want them to optimise, like error-correction and predictive accuracy, and less incentivised to optimise bureaucratic process, prestige, and signalling as our institutions now do; b) institutions are incentivised to build high performance teams rather than make this practically illegal at the apex of government; and c) we have ‘immune systems’ based on decentralisation and distributed control to minimise the inevitable failures of even the best people and teams.

Example 1: Red Teams and pre-mortems can combat groupthink and normal cognitive biases but they are practically nowhere in the formal structure of governments. There is huge scope for a Parliament-mandated small and extremely elite Red Team operating next to, and in some senses above, the Cabinet Office to ensure diversity of opinions, fight groupthink and other standard biases, make sure lessons are learned and so on. Cost: a few million that it would recoup within weeks by stopping blunders.

Example 2: prediction tournaments/markets could improve policy and project management, with people able to ‘short’ official delivery timetables — imagine being able to short Grayling’s transport announcements, for example. In many areas new markets could help — e.g markets to allow shorting of house prices to dampen bubbles, as Chris Dillow and others have suggested. The way in which the IARPA/Tetlock work has been ignored in SW1 is proof that MPs and civil servants are not actually interested in — or incentivised to be interested in — who is right, who is actually an ‘expert’, and so on. There are tools available if new people do want to take these things seriously. Cost: a few million at most, possibly thousands, that it would recoup within a year by stopping blunders.

Example 3: we need to consider projects that could bootstrap new international institutions that help solve more general coordination problems such as the risk of accidental nuclear war. The most obvious example of a project like this I can think of is a manned international lunar base which would be useful for a) basic science, b) the practical purposes of building urgently needed near-Earth infrastructure for space industrialisation, and c) to force the creation of new practical international institutions for cooperation between Great Powers. George Mueller’s team that put man on the moon in 1969 developed a plan to do this that would have been built by now if their plans had not been tragically abandoned in the 1970s. Jeff Bezos is explicitly trying to revive the Mueller vision and Britain should be helping him do it much faster. The old institutions like the UN and EU — built on early 20th Century assumptions about the performance of centralised bureaucracies — are incapable of solving global coordination problems. It seems to me more likely that institutions with qualities we need are much more likely to emerge out of solving big problems than out of think tank papers about reforming existing institutions. Cost = 10s/100s of billions, return = trillions, or near infinite if shifting our industrial/psychological frontiers into space drastically reduces the chances of widespread destruction.

A) Some fields have fantastic predictive models and there is a huge amount of high quality research, though there is a lot of low-hanging fruit in bringing methods from one field to another.

B) We know a lot about high performance including ‘systems management’ for complex projects but very few organisations use this knowledge and government institutions overwhelmingly try to ignore and suppress the knowledge we have.

C) Some fields have amazing tools for prediction and visualisation but very few organisations use these tools and almost nobody in government (where colour photocopying is a major challenge).

D) We know a lot about successful communication but very few organisations use this knowledge and most base action on false ideas. E.g political parties spend millions on spreading ideas but almost nothing on thinking about whether the messages are psychologically compelling or their methods/distribution work, and TV companies spend billions on news but almost nothing understanding what science says about how to convey complex ideas — hence why you see massively overpaid presenters like Evan Davis babbling metaphors like ‘economic takeoff’ in front of an airport while his crew films a plane ‘taking off’, or ‘the economy down the plughole’ with pictures of — a plughole.

E) Many thousands worldwide are thinking about all sorts of big government issues but very few can bring them together into coherent plans that a government can deliver and there is almost no application of things like Red Teams and prediction markets. E.g it is impossible to describe the extent to which politicians in Britain do not even consider ‘the timetable and process for turning announcement X into reality’ as something to think about — for people like Cameron and Blair the announcement IS the only reality and ‘management’ is a dirty word for junior people to think about while they focus on ‘strategy’. As I have pointed out elsewhere, it is fascinating that elite business schools have been collecting billions in fees to teach their students WRONGLY that operational excellence is NOT a source of competitive advantage, so it is no surprise that politicians and bureaucrats get this wrong.

But I can see almost nobody integrating the very best knowledge we have about A+B+C+D with E and I strongly suspect there are trillion dollar bills lying on the ground that could be grabbed for trivial cost — trillion dollar bills that people with power are not thinking about and are incentivised not to think about. I might be wrong but I would remind readers that Vote Leave was itself a bet on this proposition being right and I think its success should make people update their beliefs on the competence of elite political institutions and the possibilities for improvement.

Here I want to explore one set of intersections — the ideas of Bret Victor and Michael Nielsen.

*

2. Bret Victor: Cognitive technologies, dynamic tools, interactive quantitative models, Seeing Rooms — making it as easy to insert facts, data, and models in political discussion as it is to insert emoji

In the 1960s visionaries such as Joseph Licklider, Robert Taylor and Doug Engelbart developed a vision of networked interactive computing that provided the foundation not just for new technologies (the internet, PC etc) but for whole new industries. Licklider, Sutherland,Taylor et al provided a model (ARPA) for how science funding can work. Taylor provided a model (PARC) of how to manage a team of extremely talented people who turned a profound vision into reality. The original motivation for the vision of networked interactive computing was to help humans make good decisions in a complex world — or, ‘augmenting human intelligence’ and ‘man-machine symbiosis’. This story shows how to make big improvements in the world with very few resources if they are structured right: PARC involved ~25 key people and tens of millions over roughly a decade and generated trillions of dollars in value. If interested in the history and the super-productive processes behind the success of ARPA-PARC read THIS.

It’s fascinating that in many ways the original 1960s Licklider vision has still not been implemented. The Silicon Valley ecosystem developed parts of the vision but not others for complex reasons I don’t understand (cf. The Future of Programming). One of those who is trying to implement parts of the vision that have not been implemented is Bret Victor. Bret Victor is a rare thing: a genuine visionary in the computing world according to some of those ‘present at the creation’ of ARPA-PARC such as Alan Kay. His ideas lie at critical intersections between fields sketched above. Watch talks such as Inventing on Principle and Media for Thinking the Unthinkable and explore his current project, Dynamic Land in Berkeley.

Victor has described, and now demonstrates in Dynamic Land, how existing tools fail and what is possible. His core principle is that creators need an immediate connection to what they are creating. Current programming languages and tools are mostly based on very old ideas before computers even had screens and there was essentially no interactivity — they date from the era of punched cards. They do not allow users to interact dynamically. New dynamic tools enable us to think previously unthinkable thoughts and allow us to see and interact with complex systems: to see inside, see across time, and see across possibilities.

I strongly recommend spending a few days exploring his his whole website but I will summarise below his ideas on two things:

- His ideas about how to build new dynamic tools for working with data and interactive models.

- His ideas about transforming the physical spaces in which teams work so that dynamic tools are embedded in their environment — people work inside a tool.

Applying these ideas would radically improve how people make decisions in government and how the media reports politics/government.

Language and writing were cognitive technologies created thousands of years ago which enabled us to think previously unthinkable thoughts. Mathematical notation did the same over the past 1,000 years. For example, take a mathematics problem described by the 9th Century mathematician al-Khwarizmi (who gave us the word algorithm):

Once modern notation was invented, this could be written instead as:

x2 + 10x = 39

Michael Nielsen uses a similar analogy. Descartes and Fermat demonstrated that equations can be represented on a diagram and a diagram can be represented as an equation. This was a new cognitive technology, a new way of seeing and thinking: algebraic geometry. Changes to the ‘user interface’ of mathematics were critical to its evolution and allowed us to think unthinkable thoughts (Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Human Intelligence, see below).

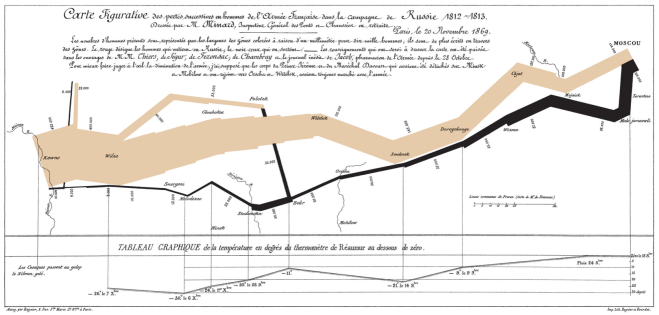

Similarly in the 18th Century, there was the creation of data graphics to demonstrate trade figures. Before this, people could only read huge tables. This is the first data graphic:

The Jedi of data visualisation, Edward Tufte, describes this extraordinary graphic of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia as ‘probably the best statistical graphic ever drawn’. It shows the losses of Napoleon’s army: from the Polish-Russian border, the thick band shows the size of the army at each position, the path of Napoleon’s winter retreat from Moscow is shown by the dark lower band, which is tied to temperature and time scales (you can see some of the disastrous icy river crossings famously described by Tolstoy). NB. The Cabinet makes life-and-death decisions now with far inferior technology to this from the 19th Century (see below).

If we look at contemporary scientific papers they represent extremely compressed information conveyed through a very old fashioned medium, the scientific journal. Printed journals are centuries old but the ‘modern’ internet versions are usually similarly static. They do not show the behaviour of systems in a visual interactive way so we can see the connections between changing values in the models and changes in behaviour of the system. There is no immediate connection. Everything is pretty much the same as a paper and pencil version of a paper. In Media for Thinking the Unthinkable, Victor shows how dynamic tools can transform normal static representations so systems can be explored with immediate feedback. This dramatically shows how much more richly and deeply ideas can be explored. With Victor’s tools we can interact with the systems described and immediately grasp important ideas that are hidden in normal media.

Picture: the very dense writing of a famous paper (by chance the paper itself is at the intersection of politics/technology and Watts has written excellent stuff on fake news but has been ignored because it does not fit what ‘the educated’ want to believe)

Picture: the same information presented differently. Victor’s tools make the information less compressed so there’s less work for the brain to do ‘decompressing’. They not only provide visualisations but the little ‘sliders’ over the graphics are to drag buttons and interact with the data so you see the connection between changing data and changing model. A dynamic tool transforms a scientific paper from ‘pencil and paper’ technology to modern interactive technology.

Victor’s essay on climate change

Victor explains in detail how policy analysis and public debate of climate change could be transformed. Leave aside the subject matter — of course it’s extremely important, anybody interested in this issue will gain from reading the whole thing and it would be great material for a school to use for an integrated science / economics / programming / politics project, but my focus is on his ideas about tools and thinking, not the specific subject matter.

Climate change is a great example to consider because it involves a) a lot of deep scientific knowledge, b) complex computer modelling which is understood in detail by a tiny fraction of 1% (and almost none of the social science trained ‘experts’ who are largely responsible for interpreting such models for politicians/journalists, cf HERE for the science of this), c) many complex political, economic, cultural issues, d) very tricky questions about how policy is discussed in mainstream culture, and e) the problem of how governments try to think about and act on important, complex, and long-term problems. Scientific knowledge is crucial but it cannot by itself answer the question: what to do? The ideas BV describes to transform the debate on climate change apply generally to how we approach all important political issues.

In the section Languages for technical computing, BV describes his overall philosophy (if you look at the original you will see dynamic graphics to help make each point but I can’t make them play on my blog — a good example of the failure of normal tools!):

‘The goal of my own research has been tools where scientists see what they’re doing in realtime, with immediate visual feedback and interactive exploration. I deeply believe that a sea change in invention and discovery is possible, once technologists are working in environments designed around:

- ubiquitous visualization and in-context manipulation of the system being studied;

- actively exploring system behavior across multiple levels of abstraction in parallel;

- visually investigating system behavior by transforming, measuring, searching, abstracting;

- seeing the values of all system variables, all at once, in context;

- dynamic notations that embed simulation, and show the effects of parameter changes;

- visually improvising special-purpose dynamic visualizations as needed.’

He then describes how the community of programming language developers have failed to create appropriate languages for scientists, which I won’t go into but which is fascinating.

He then describes the problem of how someone can usefully get to grips with a complex policy area involving technological elements.

‘How can an eager technologist find their way to sub-problems within other people’s projects where they might have a relevant idea? How can they be exposed to process problems common across many projects?… She wishes she could simply click on “gas turbines”, and explore the space:

- What are open problems in the field?

- Who’s working on which projects?

- What are the fringe ideas?

- What are the process bottlenecks?

- What dominates cost? What limits adoption?

- Why make improvements here? How would the world benefit?

‘None of this information is at her fingertips. Most isn’t even openly available — companies boast about successes, not roadblocks. For each topic, she would have to spend weeks tracking down and meeting with industry insiders. What she’d like is a tool that lets her skim across entire fields, browsing problems and discovering where she could be most useful…

‘Suppose my friend uncovers an interesting problem in gas turbines, and comes up with an idea for an improvement. Now what?

- Is the improvement significant?

- Is the solution technically feasible?

- How much would the solution cost to produce?

- How much would it need to cost to be viable?

- Who would use it? What are their needs?

- What metrics are even relevant?

‘Again, none of this information is at her fingertips, or even accessible. She’d have to spend weeks doing an analysis, tracking down relevant data, getting price quotes, talking to industry insiders.

‘What she’d like are tools for quickly estimating the answers to these questions, so she can fluidly explore the space of possibilities and identify ideas that have some hope of being important, feasible, and viable.

‘Consider the Plethora on-demand manufacturing service, which shows the mechanical designer an instant price quote, directly inside the CAD software, as they design a part in real-time. In what other ways could inventors be given rapid feedback while exploring ideas?’

Victor then describes a public debate over a public policy. Ideas were put forward. Everybody argued.

‘Who to believe? The real question is — why are readers and decision-makers forced to “believe” anything at all? Many claims made during the debate offered no numbers to back them up. Claims with numbers rarely provided context to interpret those numbers. And never — never! — were readers shown the calculations behind any numbers. Readers had to make up their minds on the basis of hand-waving, rhetoric, bombast.’

And there was no progress because nobody could really learn from the debate or even just be clear about exactly what was being proposed. Sound familiar?!! This is absolutely normal and Victor’s description applies to over 99% of public policy debates.

Victor then describes how you can take the policy argument he had sketched and change its nature. Instead of discussing words and stories, DISCUSS INTERACTIVE MODELS.

Here you need to click to the original to understand the power of what he is talking about as he programs a simple example.

‘The reader can explore alternative scenarios, understand the tradeoffs involved, and come to an informed conclusion about whether any such proposal could be a good decision.

‘This is possible because the author is not just publishing words. The author has provided a model — a set of formulas and algorithms that calculate the consequences of a given scenario… Notice how the model’s assumptions are clearly visible, and can even be adjusted by the reader.

‘Readers are thus encouraged to examine and critique the model. If they disagree, they can modify it into a competing model with their own preferred assumptions, and use it to argue for their position. Model-driven material can be used as grounds for an informed debate about assumptions and tradeoffs.

‘Modeling leads naturally from the particular to the general. Instead of seeing an individual proposal as “right or wrong”, “bad or good”, people can see it as one point in a large space of possibilities. By exploring the model, they come to understand the landscape of that space, and are in a position to invent better ideas for all the proposals to come. Model-driven material can serve as a kind of enhanced imagination.‘

Victor then looks at some standard materials from those encouraging people to take personal action on climate change and concludes:

‘These are lists of proverbs. Little action items, mostly dequantified, entirely decontextualized. How significant is it to “eat wisely” and “trim your waste”? How does it compare to other sources of harm? How does it fit into the big picture? How many people would have to participate in order for there to be appreciable impact? How do you know that these aren’t token actions to assauge guilt?

‘And why trust them? Their rhetoric is catchy, but so is the horrific “denialist” rhetoric from the Cato Institute and similar. When the discussion is at the level of “trust me, I’m a scientist” and “look at the poor polar bears”, it becomes a matter of emotional appeal and faith, a form of religion.

‘Climate change is too important for us to operate on faith. Citizens need and deserve reading material which shows context — how significant suggested actions are in the big picture — and which embeds models — formulas and algorithms which calculate that significance, for different scenarios, from primary-source data and explicit assumptions.’

Even the supposed ‘pros’ — Insiders at the top of research fields in politically relevant areas — have to scramble around typing words into search engines, crawling around government websites, and scrolling through PDFs. Reliable data takes ages to find. Reliable models are even harder to find. Vast amounts of useful data and models exist but they cannot be found and used effectively because we lack the tools.

‘Authoring tools designed for arguing from evidence’

Why don’t we conduct public debates in the way his toy example does with interactive models? Why aren’t paragraphs in supposedly serious online newspapers written like this? Partly because of the culture, including the education of those who run governments and media organisations, but also because the resources for creating this sort of material don’t exist.

‘In order for model-driven material to become the norm, authors will need data, models, tools, and standards…

‘Suppose there were good access to good data and good models. How would an author write a document incorporating them? Today, even the most modern writing tools are designed around typing in words, not facts. These tools are suitable for promoting preconceived ideas, but provide no help in ensuring that words reflect reality, or any plausible model of reality. They encourage authors to fool themselves, and fool others…

‘Imagine an authoring tool designed for arguing from evidence. I don’t mean merely juxtaposing a document and reference material, but literally “autocompleting” sourced facts directly into the document. Perhaps the tool would have built-in connections to fact databases and model repositories, not unlike the built-in spelling dictionary. What if it were as easy to insert facts, data, and models as it is to insert emoji and cat photos?

‘Furthermore, the point of embedding a model is that the reader can explore scenarios within the context of the document. This requires tools for authoring “dynamic documents” — documents whose contents change as the reader explores the model. Such tools are pretty much non-existent.’

These sorts of tools for authoring dynamic documents should be seen as foundational technology like the integrated circuit or the internet.

‘Foundational technology appears essential only in retrospect. Looking forward, these things have the character of “unknown unknowns” — they are rarely sought out (or funded!) as a solution to any specific problem. They appear out of the blue, initially seem niche, and eventually become relevant to everything.

‘They may be hard to predict, but they have some common characteristics. One is that they scale well. Integrated circuits and the internet both scaled their “basic idea” from a dozen elements to a billion. Another is that they are purpose-agnostic. They are “material” or “infrastructure”, not applications.’

Victor ends with a very potent comment — that much of what we observe is ‘rearranging app icons on the deck of the Titanic’. Commercial incentives drive people towards trying to create ‘the next Facebook’ — not fixing big social problems. I will address this below.

If you are an arts graduate interested in these subjects but not expert (like me), here is an example that will be more familiar… If you look at any big historical subject, such as ‘why/how did World War I start?’ and examine leading scholarship carefully, you will see that all the leading books on such subjects provide false chronologies and mix facts with errors such that it is impossible for a careful reader to be sure about crucial things. It is routine for famous historians to write that ‘X happened because Y’ when Y happened after X. Part of the problem is culture but this could potentially be improved by tools. A very crude example: why doesn’t Kindle make it possible for readers to log factual errors, with users’ reliability ranked by others, so authors can easily check potential errors and fix them in online versions of books? Even better, this could be part of a larger system to develop gold standard chronologies with each ‘fact’ linked to original sources and so on. This would improve the reliability of historical analysis and it would create an ‘anti-entropy’ ratchet — now, entropy means that errors spread across all books on a subject and there is no mechanism to reverse this…

‘Seeing Rooms’: macro-tools to help make decisions

Victor also discusses another fundamental issue: the rooms/spaces in which most modern work and thinking occurs are not well-suited to the problems being tackled and we could do much better. Victor is addressing advanced manufacturing and robotics but his argument applies just as powerfully, perhaps more powerfully, to government analysis and decision-making.

Now, ‘software based tools are trapped in tiny rectangles’. We have very sophisticated tools but they all sit on computer screens on desks, just as you are reading this blog.

In contrast, ‘Real-world tools are in rooms where workers think with their bodies.’ Traditional crafts occur in spatial environments designed for that purpose. Workers walk around, use their hands, and think spatially. ‘The room becomes a macro-tool they’re embedded inside, an extension of the body.’ These rooms act like tools to help them understand their problems in detail and make good decisions.

Picture: rooms designed for the problems being tackled

The wave of 3D printing has developed ‘maker rooms’ and ‘Fab Labs’ where people work with a set of tools that are too expensive for an individual. The room is itself a network of tools. This approach is revolutionising manufacturing.

Why is this useful?

‘Modern projects have complex behavior… Understanding requires seeing and the best seeing tools are rooms.’ This is obviously particularly true of politics and government.

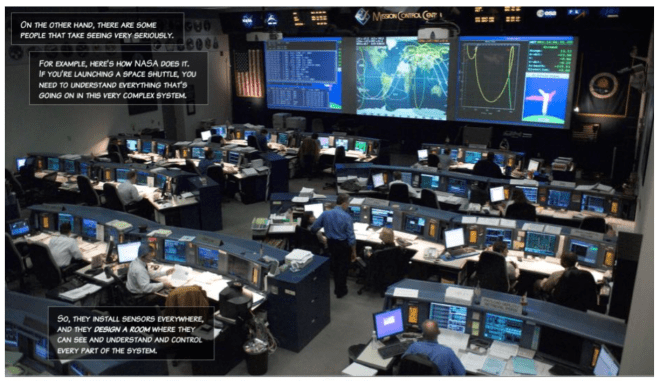

Here is a photo of a recent NASA mission control room. The room is set up so that all relevant people can see relevant data and models at different scales and preserve a common picture of what is important. NASA pioneered thinking about such rooms and the technology and tools needed in the 1960s.

Here are pictures of two control rooms for power grids.

Here is a panoramic photo of the unified control centre for the Large Hadron Collider – the biggest of ‘big data’ projects. Notice details like how they have removed all pillars so nothing interrupts visual communication between teams.

Now contrast these rooms with rooms from politics.

Here is the Cabinet room. I have been in this room. There are effectively no tools. In the 19th Century at least Lord Salisbury used the fireplace as a tool. He would walk around the table, gather sensitive papers, and burn them at the end of meetings. The fire is now blocked. The only other tool, the clock, did not work when I was last there. Over a century, the physical space in which politicians make decisions affecting potentially billions of lives has deteriorated.

British Cabinet room practically as it was July 1914

Here are JFK and EXCOM making decisions during the Cuban Missile Crisis that moved much faster than July 1914, compressing decisions leading to the destruction of global civilisation potentially into just minutes.

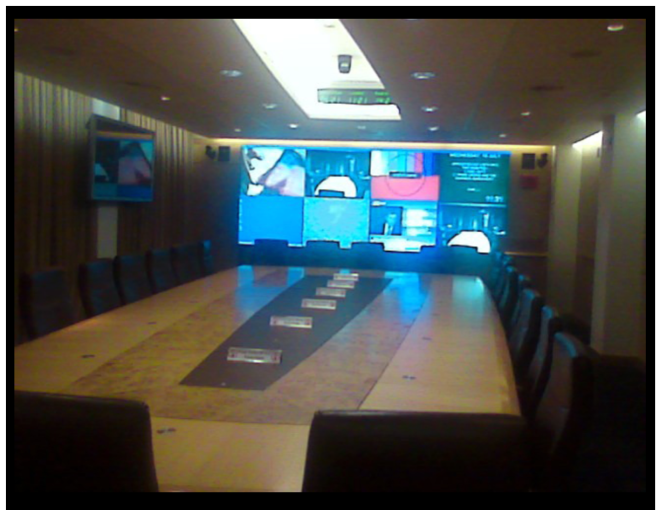

Here is the only photo in the public domain of the room known as ‘COBRA’ (Cabinet Office Briefing Room) where a shifting set of characters at the apex of power in Britain meet to discuss crises.

Notice how poor it is compared to NASA, the LHC etc. There has clearly been no attempt to learn from our best examples about how to use the room as a tool. The screens at the end are a late add-on to a room that is essentially indistinguishable from the room in which Prime Minister Asquith sat in July 1914 while doodling notes to his girlfriend as he got bored. I would be surprised if the video technology used is as good as what is commercially available cheaper, the justification will be ‘security’, and I would bet that many of the decisions about the operation of this room would not survive scrutiny from experts in how to construct such rooms.

I have not attended a COBRA meeting but I’ve spoken to many who have. The meetings, as you would expect looking at this room, are often normal political meetings. That is:

- aims are unclear,

- assumptions are not made explicit,

- there is no use of advanced tools,

- there is no use of quantitative models,

- discussions are often dominated by lawyers so many actions are deemed ‘unlawful’ without proper scrutiny (and this device is routinely used by officials to stop discussion of options they dislike for non-legal reasons),

- there is constant confusion between policy, politics and PR then the cast disperses without clarity about what was discussed and agreed.

Here is a photo of the American equivalent – the Situation Room.

It has a few more screens but the picture is essentially the same: there are no interactive tools beyond the ability to speak and see someone at a distance which was invented back in the 1950s/1960s in the pioneering programs of SAGE (automated air defence) and Apollo (man on the moon). Tools to help thinking in powerful ways are not taken seriously. It is largely the same, and decisions are made the same, as in the Cuban Missile Crisis. In some ways the use of technology now makes management worse as it encourages Presidents and their staff to try to micromanage things they should not be managing, often in response to or fear of the media.

Individual ministers’ officers are also hopeless. The computers are old and rubbish. Even colour printing is often a battle. Walls are for kids’ pictures. In the DfE officials resented even giving us paper maps of where schools were and only did it when bullied by the private office. It was impossible for officials to work on interactive documents. They had no technology even for sharing documents in a way that was then (2011) normal even in low-performing organisations. Using GoogleDocs was ‘against the rules’. (I’m told this has slightly improved.) The whole structure of ‘submissions’ and ‘red boxes’ is hopeless. It is extremely bureaucratic and slow. It prevents serious analysis of quantitative models. It reinforces the lack of proper scientific thinking in policy analysis. It guarantees confusion as ministers scribble notes and private offices interpret rushed comments by exhausted ministers after dinner instead of having proper face-to-face meetings that get to the heart of problems and resolve conflicts quickly. The whole approach reinforces the abject failure of the senior civil service to think about high performance project management.

Of course, most of the problems with the standards of policy and management in the civil service are low or no-tech problems — they involve the ‘unrecognised simplicities’ that are independent of, and prior to, the use of technology — but all these things negatively reinforce each other. Anybody who wants to do things much better is scuppered by Whitehall’s entangled disaster zone of personnel, training, management, incentives and tools.

*

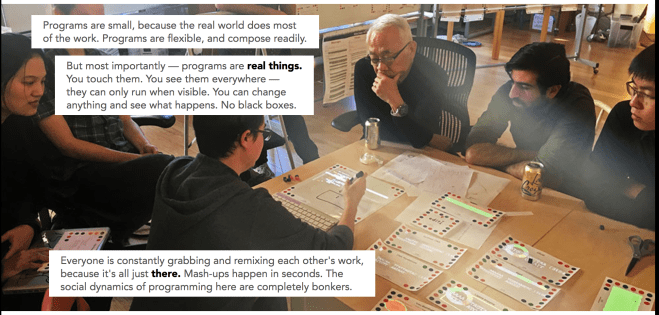

Dynamic Land: ‘amazing’

I won’t go into this in detail. Dynamic Land is in a building in Berkeley. I visited last year. It is Victor’s attempt to turn the ideas above into a sort of living laboratory. It is a large connected set of rooms that have computing embedded in surfaces. For example, you can scribble equations on a bit of paper, cameras in the ceiling read your scribbles automatically, turn them into code, and execute them — for example, by producing graphics. You can then physically interact with models that appear on the table or wall while the cameras watch your hands and instantly turn gestures into new code and change the graphics or whatever you are doing. Victor has put these cutting edge tools into a space and made it open to the Berkeley community. This is all hard to explain/understand because you haven’t seen anything like it even in sci-fi films (it’s telling the media still uses the 15 year-old Minority Report as its sci-fi illustration for such things).

This video gives a little taste. I visited with a physicist who works on the cutting edge of data science/AI. I was amazed but I know nothing about such things — I was interested to see his reaction as he scribbled gravitational equations on paper and watched the cameras turn them into models on the table in real-time, then he changed parameters and watched the graphics change in real-time on the table (projected from the ceiling): ‘Ohmygod, this is just obviously the future, absolutely amazing.’ The thought immediately struck us: imagine the implications of having policy discussions with such tools instead of the usual terrible meetings. Imagine discussing HS2 budgets or possible post-Brexit trading arrangements with the models running like this for decision-makers to interact with.

Video of Dynamic Land: the bits of coloured paper are ‘code’, graphics are projected from the ceiling

*

3. Michael Nielsen and cognitive technologies

Connected to Victor’s ideas are those of the brilliant physicist, Michael Nielsen. Nielsen wrote the textbook on quantum computation and a great book, Reinventing Discovery, on the evolution of the scientific method. For example, instead of waiting for the coincidence of Grossmann helping out Einstein with some crucial maths, new tools could create a sort of ‘designed serendipity’ to help potential collaborators find each other.

In his essay Thought as a Technology, Nielsen describes the feedback between thought and interfaces:

‘In extreme cases, to use such an interface is to enter a new world, containing objects and actions unlike any you’ve previously seen. At first these elements seem strange. But as they become familiar, you internalize the elements of this world. Eventually, you become fluent, discovering powerful and surprising idioms, emergent patterns hidden within the interface. You begin to think with the interface, learning patterns of thought that would formerly have seemed strange, but which become second nature. The interface begins to disappear, becoming part of your consciousness. You have been, in some measure, transformed.’

He describes how normal language and computer interfaces are cognitive technologies:

‘Language is an example of a cognitive technology: an external artifact, designed by humans, which can be internalized, and used as a substrate for cognition. That technology is made up of many individual pieces – words and phrases, in the case of language – which become basic elements of cognition. These elements of cognition are things we can think with…

‘In a similar way to language, maps etc, a computer interface can be a cognitive technology. To master an interface requires internalizing the objects and operations in the interface; they become elements of cognition. A sufficiently imaginative interface designer can invent entirely new elements of cognition… In general, what makes an interface transformational is when it introduces new elements of cognition that enable new modes of thought. More concretely, such an interface makes it easy to have insights or make discoveries that were formerly difficult or impossible. At the highest level, it will enable discoveries (or other forms of creativity) that go beyond all previous human achievement.’

Nielsen describes how powerful ways of thinking among mathematicians and physicists are hidden from view and not part of textbooks and normal teaching.

‘The reason is that traditional media are poorly adapted to working with such representations… If experts often develop their own representations, why do they sometimes not share those representations? To answer that question, suppose you think hard about a subject for several years… Eventually you push up against the limits of existing representations. If you’re strongly motivated – perhaps by the desire to solve a research problem – you may begin inventing new representations, to provide insights difficult through conventional means. You are effectively acting as your own interface designer. But the new representations you develop may be held entirely in your mind, and so are not constrained by traditional static media forms. Or even if based on static media, they may break social norms about what is an “acceptable” argument. Whatever the reason, they may be difficult to communicate using traditional media. And so they remain private, or are only discussed informally with expert colleagues.’

If we can create interfaces that reify deep principles, then ‘mastering the subject begins to coincide with mastering the interface.’ He gives the example of Photoshop which builds in many deep principles of image manipulation.

‘As you master interface elements such as layers, the clone stamp, and brushes, you’re well along the way to becoming an expert in image manipulation… By contrast, the interface to Microsoft Word contains few deep principles about writing, and as a result it is possible to master Word‘s interface without becoming a passable writer. This isn’t so much a criticism of Word, as it is a reflection of the fact that we have relatively few really strong and precise ideas about how to write well.’

He then describes what he calls ‘the cognitive outsourcing model’: ‘we specify a problem, send it to our device, which solves the problem, perhaps in a way we-the-user don’t understand, and sends back a solution.’ E.g we ask Google a question and Google sends us an answer.

This is how most of us think about the idea of augmenting the human intellect but it is not the best approach. ‘Rather than just solving problems expressed in terms we already understand, the goal is to change the thoughts we can think.’

‘One challenge in such work is that the outcomes are so difficult to imagine. What new elements of cognition can we invent? How will they affect the way human beings think? We cannot know until they’ve been invented.

‘As an analogy, compare today’s attempts to go to Mars with the exploration of the oceans during the great age of discovery. These appear similar, but while going to Mars is a specific, concrete goal, the seafarers of the 15th through 18th centuries didn’t know what they would find. They set out in flimsy boats, with vague plans, hoping to find something worth the risks. In that sense, it was even more difficult than today’s attempts on Mars.

‘Something similar is going on with intelligence augmentation. There are many worthwhile goals in technology, with very specific ends in mind. Things like artificial intelligence and life extension are solid, concrete goals. By contrast, new elements of cognition are harder to imagine, and seem vague by comparison. By definition, they’re ways of thinking which haven’t yet been invented. There’s no omniscient problem-solving box or life-extension pill to imagine. We cannot say a priori what new elements of cognition will look like, or what they will bring. But what we can do is ask good questions, and explore boldly.

In another essay, Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Human Intelligence, Nielsen points out that breakthroughs in creating powerful new cognitive technologies such as musical notation or Descartes’ invention of algebraic geometry are rare but ‘modern computers are a meta-medium enabling the rapid invention of many new cognitive technologies‘ and, further, AI will help us ‘invent new cognitive technologies which transform the way we think.’

Further, historically powerful new cognitive technologies, such as ‘Feynman diagrams’, have often appeared strange at first. We should not assume that new interfaces should be ‘user friendly’. Powerful interfaces that repay mastery may require sacrifices.

‘The purpose of the best interfaces isn’t to be user-friendly in some shallow sense. It’s to be user-friendly in a much stronger sense, reifying deep principles about the world, making them the working conditions in which users live and create. At that point what once appeared strange can instead becomes comfortable and familiar, part of the pattern of thought…

‘Unfortunately, many in the AI community greatly underestimate the depth of interface design, often regarding it as a simple problem, mostly about making things pretty or easy-to-use. In this view, interface design is a problem to be handed off to others, while the hard work is to train some machine learning system.

‘This view is incorrect. At its deepest, interface design means developing the fundamental primitives human beings think and create with. This is a problem whose intellectual genesis goes back to the inventors of the alphabet, of cartography, and of musical notation, as well as modern giants such as Descartes, Playfair, Feynman, Engelbart, and Kay. It is one of the hardest, most important and most fundamental problems humanity grapples with.

‘As discussed earlier, in one common view of AI our computers will continue to get better at solving problems, but human beings will remain largely unchanged. In a second common view, human beings will be modified at the hardware level, perhaps directly through neural interfaces, or indirectly through whole brain emulation.

‘We’ve described a third view, in which AIs actually change humanity, helping us invent new cognitive technologies, which expand the range of human thought. Perhaps one day those cognitive technologies will, in turn, speed up the development of AI, in a virtuous feedback cycle:

‘It would not be a Singularity in machines. Rather, it would be a Singularity in humanity’s range of thought… The long-term test of success will be the development of tools which are widely used by creators. Are artists using these tools to develop remarkable new styles? Are scientists in other fields using them to develop understanding in ways not otherwise possible?’

I would add: are governments using these tools to help them think in ways we already know are more powerful and to explore new ways of making decisions and shaping the complex systems on which we rely?

Nielsen also wrote this fascinating essay ‘Augmenting long-term memory’. This involves a computer tool (Anki) to aid long-term memory using ‘spaced repetition’ — i.e testing yourself at intervals which is shown to counter the normal (for most people) process of forgetting. This allows humans to turn memory into a choice so we can decide what to remember and achieve it systematically (without a ‘weird/extreme gift’ which is how memory is normally treated). (It’s fascinating that educated Greeks 2,500 years ago could build sophisticated mnemonic systems allowing them to remember vast amounts while almost all educated people now have no idea about such techniques.)

Connected to this, Nielsen also recently wrote an essay teaching fundamentals of quantum mechanics and quantum computers — but it is an essay with a twist:

‘[It] incorporates new user interface ideas to help you remember what you read… this essay isn’t just a conventional essay, it’s also a new medium, a mnemonic medium which integrates spaced-repetition testing. The medium itself makes memory a choice… This essay will likely take you an hour or two to read. In a conventional essay, you’d forget most of what you learned over the next few weeks, perhaps retaining a handful of ideas. But with spaced-repetition testing built into the medium, a small additional commitment of time means you will remember all the core material of the essay. Doing this won’t be difficult, it will be easier than the initial read. Furthermore, you’ll be able to read other material which builds on these ideas; it will open up an entire world…

‘Mastering new subjects requires internalizing the basic terminology and ideas of the subject. The mnemonic medium should radically speed up this memory step, converting it from a challenging obstruction into a routine step. Frankly, I believe it would accelerate human progress if all the deepest ideas of our civilization were available in a form like this.’

This obviously has very important implications for education policy. It also shows how computers could be used to improve learning — something that has generally been a failure since the great hopes at PARC in the 1970s. I have used Anki since reading Nielsen’s blog and I can feel it making a big difference to my mind/thoughts — how often is this true of things you read? DOWNLOAD ANKI NOW AND USE IT!

We need similarly creative experiments with new mediums that are designed to improve standards of high stakes decision-making.

*

4. Summary

We could create systems for those making decisions about m/billions of lives and b/trillions of dollars, such as Downing Street or The White House, that integrate inter alia:

- Cognitive toolkits compressing already existing useful knowledge such as checklists for rational thinking developed by the likes of Tetlock, Munger, Yudkowsky et al.

- A Nielsen/Victor research program on ‘Seeing Rooms’, interface design, authoring tools, and cognitive technologies. Start with bunging a few million to Victor immediately in return for allowing some people to study what he is doing and apply it in Whitehall, then grow from there.

- An alpha data science/AI operation — tapping into the world’s best minds including having someone like David Deutsch or Tim Gowers as a sort of ‘chief rationalist’ in the Cabinet (with Scott Alexander as deputy!) — to support rational decision-making where this is possible and explain when it is not possible (just as useful).

- Tetlock/Hanson prediction tournaments could easily and cheaply be extended to consider ‘clusters’ of issues around themes like Brexit to improve policy and project management.

- Groves/Mueller style ‘systems management’ integrated with the data science team.

- Legally entrenched Red Teams where incentives are aligned to overcoming groupthink and error-correction of the most powerful. Warren Buffett points out that public companies considering an acquisition should employ a Red Team whose fees are dependent on the deal NOT going ahead. This is the sort of idea we need in No10.

Researchers could see the real operating environment of decision-makers at the apex of power, the sort of problems they need to solve under pressure, and the constraints of existing centralised systems. They could start with the safe level of ‘tools that we already know work really well’ — i.e things like cognitive toolkits and Red Teams — while experimenting with new tools and new ways of thinking.

Hedge funds like Bridgewater and some other interesting organisations think about such ideas though without the sophistication of Victor’s approach. The world of MPs, officials, the Institute for Government (a cheerleader for ‘carry on failing’), and pundits will not engage with these ideas if left to their own devices.

This is not the place to go into how to change this. We know that the normal approach is doomed to produce the normal results and normal results applied to things like repeated WMD crises means disaster sooner or later. As Buffett points out, ‘If there is only one chance in thirty of an event occurring in a given year, the likelihood of it occurring at least once in a century is 96.6%.’ It is not necessary to hope in order to persevere: optimism of the will, pessimism of the intellect…

*

A final thought…

A very interesting comment that I have heard from some of the most important scientists involved in the creation of advanced technologies is that ‘artists see things first’ — that is, artists glimpse possibilities before most technologists and long before most businessmen and politicians.

Pixar came from a weird combination of George Lucas getting divorced and the visionary Alan Kay suggesting to Steve Jobs that he buy a tiny special effects unit from Lucas, which Jobs did with completely wrong expectations about what would happen. For unexpected reasons this tiny unit turned into a huge success — as Jobs put it later, he was ‘sort of snookered’ into creating Pixar. Now Alan Kay says he struggles to get tech billionaires to understand the importance of Victor’s ideas.

The same story repeats: genuinely new ideas that could create huge value always seem so odd that almost all people in almost all organisations cannot see new possibilities. If this is true in Silicon Valley, how much more true is it in Whitehall or Washington…

If one were setting up a new party in Britain, one could incorporate some of these ideas. This would of course also require recruiting very different types of people to the norm in politics. The closed nature of Westminster/Whitehall combined with first-past-the-post means it is very hard to solve the coordination problem of how to break into this system with a new way of doing things. Even those interested in principle don’t want to commit to a 10-year (?) project that might get them blasted on the front pages. Vote Leave hacked the referendum but such opportunities are much rarer than VC-funded ‘unicorns’. On the other hand, arguably what is happening now is a once in 50 or 100 year crisis and such crises also are the waves that can be ridden to change things normally unchangeable. A second referendum in 2020 is quite possible (or two referendums under PM Corbyn, propped up by the SNP?) and might be the ideal launchpad for a completely new sort of entity, not least because if it happens the Conservative Party may well not exist in any meaningful sense (whether there is or isn’t another referendum). It’s very hard to create a wave and it’s much easier to ride one. It’s more likely in a few years you will see some of the above ideas in novels or movies or video games than in government — their pickup in places like hedge funds and intelligence services will be discrete — but you never know…

*

Ps. While I have talked to Michael Nielsen and Bret Victor about their ideas, in no way should this blog be taken as their involvement in anything to do with my ideas or plans or agreement with anything written above. I did not show this to them or even tell them I was writing about their work, we do not work together in any way, I have just read and listened to their work over a few years and thought about how their ideas could improve government.

Further Reading

If interested in how to make things work much better, read this (lessons for government from the Apollo project) and this (lessons for government from ARPA-PARC’s creation of the internet and PC).